Your cart is currently empty!

Fake Corpses and Real Fun: Exploring Social Frames in Pervasive Games

[日本語版が下にあります]

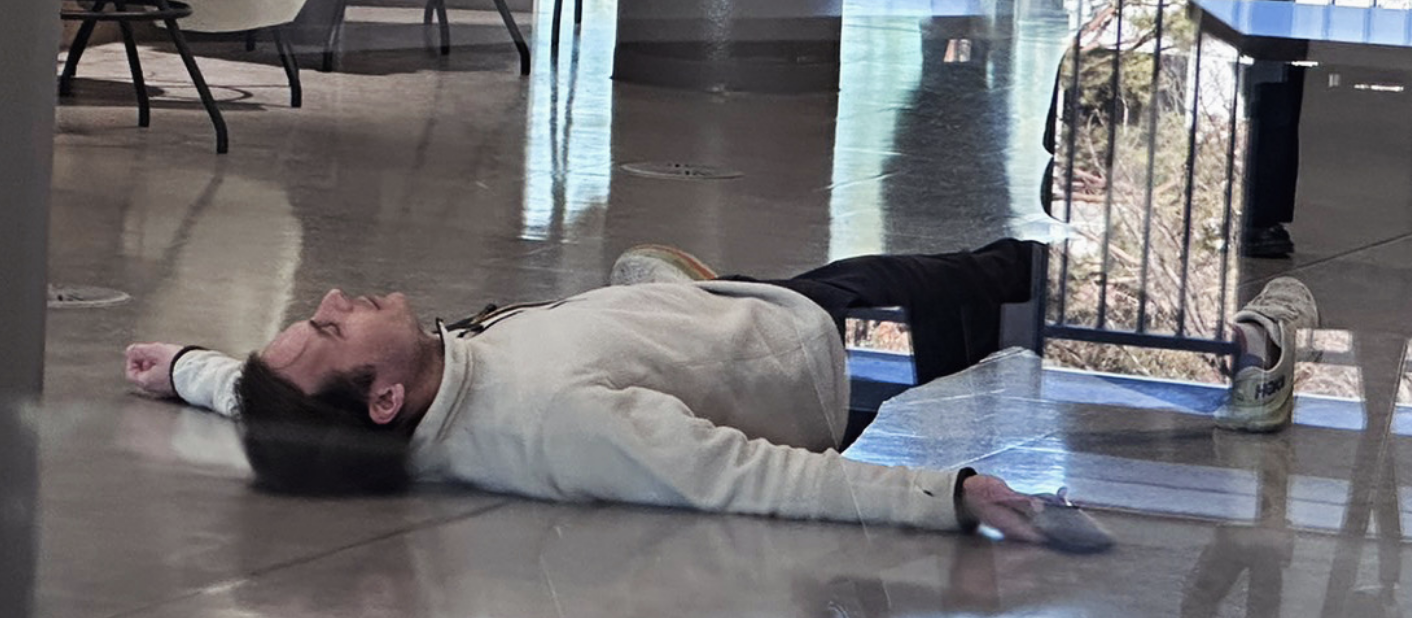

Figure 1: I lie dead on the floor surrounded by students going about their day.

Some are working on their essays, homework, and other academic pursuits. Some are relaxing, eating, or just going along with their day. None of them know why I’m lying on the floor. None of them know that I’m dead. Soon, a single student comes over. He doesn’t try and resuscitate me. He doesn’t see anything strange with me lying on the floor in a public space. He just takes a quick photo, calls in my death to the rest of the team, and walks away.

This is not normal, is it? So, how did this situation come about?

In this short essay I’ll answer:

- Why I’m lying dead on the floor

- What it has to do with Suit’s Lusory Attitude and the Magic Circle

- Why any of this is important

- How this relates to our ways of being (frames) in society

1: Why I’m lying dead on the floor

I’m not really dead. Obviously. I’m playing a student-made, pervasive game based on the popular mobile game “Among Us.” If you don’t know it, here’s a quick description of the game:

— 🧑🚀–

Among Us is a multiplayer social deduction game for 4 to 10 players. The game is set in a space station, where players must complete tasks to keep the ship running while also trying to identify and eliminate the imposters.

There are two roles in Among Us: Crewmates and Imposters.

Crewmates are tasked with completing a variety of tasks around the ship, such as fixing wiring, fueling engines, and emptying trash.

Imposters are tasked with sabotaging the ship and killing the crewmates.

The game is played in real-time, and players can communicate with each other using a chat function. Crewmates can use the chat function to discuss who they think the imposters are and to coordinate their tasks. Imposters can use the chat function to lie and deceive their crewmates to avoid being caught.

The game ends when all of the tasks are completed, or when all of the crewmates are killed. If all of the crewmates are killed, the imposters win. If all of the tasks are completed, the crewmates win.

BONUS: I’ve written a think piece on how Among Us could be used in language education here (York, 2020).

— 🧑🚀–

ඞ Digital version of Among Us

In the digital game, my agency to “act dead” in the spaceship is completely taken away from me. The game removes my ability to control the character avatar that represents me, and instead, I’m displayed as a kind of cartoon meat stick, bone sticking out to the left (Figure XX). I lose my character avatar and get to control a new avatar: a ghost version of myself which cannot interact with the other still-alive players.

Figure 2: A corpse avatar in the digital version of Among Us.

Source: https://among-us.fandom.com/wiki/Dead_body

ඞ Real-life version of Among Us

In this real-life version of the game, however, there is no underlying computer software, or hardcoded rules which dictate how I behave or rob my agency. I decide. I know I’m to play dead, but it’s up to me to enact it.

So, in this case, and in the photo above, I’m doing exactly what is expected of me. My actions (lying down on the fourth floor of Meiji University’s Learning Square at Izumi Campus) are completely logical, and, if anything, the only thing that I should be doing at that point in time … if you know that I’m playing a game.

That is what this essay is about — explaining why lying on the floor in public was “the right and natural thing to do” although from the outside my actions look totally the opposite.

2: The Magic Circle of Games

The pervasive nature of pervasive games

This semester in my Freshman Seminar (教養演習) students were tasked with creating a “big game” or what is known in game-design circles as a “pervasive game.” These are games that blur the boundary known as the “magic circle” between the real world and the game world. So let’s think about these concepts: game world, non-game world and the barrier(s) between the two.

The magic circle of (non-pervasive) games

One of the core concepts of game philosophy and game studies is defining where a game starts and ends in relation to non-game, real-life contexts.

The magic circle is a term coined by Dutch historian of culture Johan Huizinga in his 1938 book Homo Ludens, which describes the temporal and spatial separation of a game from the real world. According to Huizinga, the magic circle is a “temporary world in which the rules of ordinary life are suspended.” He argues that games create a special kind of reality, separate from the everyday world, in which players can experience a sense of freedom and escape. When players enter the magic circle, they agree to abide by the rules of the game. This creates a sense of shared purpose and cooperation among players, and it allows them to suspend their disbelief and enter into the game world.

As a concrete example, consider boxing. Just by observing a boxing match, we know a number of things clearly:

- Who is currently playing.

- What is and what is not allowed during play.

- Where the game is being played.

- When the game starts and ends.

These things exist within boundaries which are separate from reality. The physical boundary of the boxing ring separates the boxing match from non-boxing contexts. The social boundary tells us who is and isn’t currently engaged in the boxing match. Another boundary exists in terms of the rules of interaction which allow certain means and discount or prohibit others (that is: if one of the boxers puts horse shoes in their gloves, they are NOT boxing as we know it. They have cheated and thus NOT playing the game. Finally, the temporal boundary tells us that for 3 to 12 rounds, the two competitors are boxing. Once the time has expired (or someone loses) the game is over.

There is some debate as to whether the magic circle exists. Consalvo (2009) writes that there is no magic circle and Calleja, (2012) tried to erase it. But I’m on the side of there definitely being some kind of boundary between game and non-game context. So let’s first define it and discuss how pervasive games blur it.

Pervasive games and breaking the magic circle

Pervasive games break the magic circle of games by blurring the line between the game world and the real world. That is exactly what is happening in the case of me lying dead in the Learning Square.

As I have described above, in traditional games, the game world is a separate, self-contained space that is distinct from the real world. Players enter the game world by agreeing to abide by the rules of the game, and they leave the game world when they stop playing. (One of the biggest arguments against the magic circle here is with digital games, as the game world exists in a separate space from the real world — on screen). Pervasive games, on the other hand, do not have a clear boundary between the game world and the real world. The game world can extend into the real world, and the real world can intrude into the game world. This blurring of the boundaries between the game world and the real world can create a sense of immersion and realism for players, but it can also make it difficult to define where the game ends and the real world begins. Which is great (imo). Montola et al. (2009) describe pervasive games as games that use the physical environment as part of the game world and that require players to move through the real world to play.

How the “Real Among Us” game breaks the magic circle

It might be quite obvious, but the real Among Us game breaks/expands the magic circle in terms of physical space.

As stated, this game was played on a university campus, where people are conducting their daily activities. As a result, this game takes over space in the real world as its playground. Real Among Us penetrates the real world. The clear distinction between “this area is for playing a game” and “this area is for studying” does not exist for the players of the game. Alternatively, consider this from the perspective of non-players. They are unaware that we are playing a game. The space they are using is for the purpose of studying. This intermingling of purposes is intiitely tied to the mental state of the people in the space, specifically players vs non-players mindsets (something we’ll look at shortly).

BTW, for more on the appropriating nature of play, see Sicart, 2014, Chapter 1. I highly recommend this book!

3: Why it matters

Goffman’s Frames and the Performance of Play

So, why lie dead on the floor? Beyond the thrill of the game, this action becomes a lens through which to explore how our mental states and actions in pervasive games relate to Goffman’s theory of “frames” and our broader societal interactions.

Erving Goffman’s (1974) concept of “frames” helps us understand how we make sense of the world around us. According to Goffman, we constantly organize our experiences into interpretive frameworks, or “frames,” that provide context and meaning to our interactions. These frames help us navigate social situations by establishing what is expected and appropriate behaviour. Another important concept for us here is Suit’s (1978) notion of the “lusory attitude.” This describes the particular mental state we adopt when playing games, a willingness to suspend disbelief and accept the game’s fictional reality as our temporary frame of reference.

Now, when we combine these concepts with the unique nature of pervasive games, things get interesting. By seamlessly blending the game world with the real world, these games challenge and blur the established frames of everyday life. In my case, lying dead on the floor disrupts the expected frame of a university hallway – students studying, walking, and socializing. However, within the shared lusory frame of the game, my action is perfectly rational – a deceased crewmate performing their role.

4: Implications for Society

This blurring or shifting of frames that occurs in pervasive games doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It reflects and potentially influences the way we interact and behave in society as a whole. By encouraging us to consider different perspectives and adapt our behaviour accordingly, pervasive games could be seen as training grounds for flexibility and empathy in social interactions. Or, at least, we might realise that our day-to-day social frames are not fixed and can be changed or improved… 🤔.

Outside of pervasive gameplay, and as a concrete example of the importance of recognising our current frame, Lowe (2023) wrote a short piece about how teachers of English as a second language might suddenly recognize the lack of engagement and hollowness of some classroom activities. That is, we might stop going through the motions of teaching and become self-aware that the content is perhaps pointless for our particular students; that we are engaging students in what Pennycook (1994, p.311) calls “empty babble.” This self-awareness can prompt teachers to re-evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching methods. Thus, by stepping outside the traditional “teacher” frame and considering the students’ perspectives, they can identify content that may be pointless or irrelevant, ultimately striving to create more engaging and meaningful learning experiences.

Closing Thoughts: A Playground for Understanding

Ultimately, my dead-on-the-floor experience highlights the fascinating intersection of mental states, actions, and social frames in pervasive games. By embracing a lusory attitude (that is: to fully accept the rules of the game for the sake of bringing the game into existence) and navigating the blurred boundaries between game and reality, these games offer a unique playground for understanding ourselves and our interactions with the world around us.

Key points:

- Frames — We interpret the world through “frames” that define expected behaviour and meaning in specific situations.

- Lusory attitude — When playing games, we adopt a special mental state, accepting the game’s reality as our temporary frame.

- Pervasive games — These games blur the lines between game and reality, challenging our usual frames.

- Performance and Misinterpretation — Players perform their roles within the game’s frame, while outsiders interpret their actions through their own “normal” frame, leading to potential misunderstandings.

References

Consalvo, M. (2009). There is No Magic Circle. Games and Culture, 4(4), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009343575.

Calleja, G. (2012). Erasing the Magic Circle. In: Sageng, J., Fossheim, H., Mandt Larsen, T. (eds) The Philosophy of Computer Games. Philosophy of Engineering and Technology, vol 7. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4249-9_6

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Lowe, R. J. (2023). A note on authenticity, reflexivity, and subversion in the classroom. ELT Journal, ccad055. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccad055

Montola, M., Stenros, J., & Waern, A. (2009). Pervasive Games: Theory and Design (1st ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780080889795

Pennycook, A. (1994). The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. London: Longman

Sicart, M. (2014). Play matters: Playful thinking in a digital world. MIT Press.

Suits, B. H. (1978). The grasshopper: Games, life, and Utopia. Toronto/Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.York, J. (2020). 👩🚀 How to teach languages with “Among Us.” Ludic Language Pedagogy, 2, 269-283. https://doi.org/10.55853/llp_v2Pg11

日本語版

(自動翻訳)

図1:私は床に死んで横たわり、学生たちが日常生活を送る中に囲まれています。

いくつかの学生はエッセイや宿題、その他の学業に取り組んでいます。一部はリラックスしたり、食事をしたり、ただ日常生活を送ったりしています。彼らは誰も私が床に横たわっている理由を知りません。誰も私が死んでいることを知りません。やがて、一人の学生が近づいてきます。彼は私を蘇生しようとはしません。彼は公共の場で床に横たわっている私に何か奇妙なことは見ていません。彼はただ素早く写真を撮り、残りのチームに私の死を伝えて去っていきます。

これは普通ではないですね?では、なぜこの状況が生まれたのでしょうか?

この短いエッセイでは以下に答えます:

- 私が床に死んでいる理由

- それがスーツの遊びの態度とマジックサークルと何か関係があるのか

- なぜこれが重要なのか

- これが社会における私たちの在り方(フレーム)とどう関連しているのか

セクション1:私が床に死んでいる理由

実際には私は死んでいません。もちろんです。私は人気のあるモバイルゲーム「Among Us」を基にした学生作成の普及型ゲームをプレイしています。知らない方のために、ゲームの簡単な説明です:

| – 🧑🚀–Among Usは4〜10人のプレイヤー向けのマルチプレイヤーソーシャルデダクションゲームです。ゲームは宇宙ステーションで設定されており、プレイヤーは船を稼働させるためにタスクを完了しながらもインポスターを特定し排除しなければなりません。 Among Usには2つの役割があります:クルーメイトとインポスターです。 クルーメイトは船の周りで配線を修理したり、エンジンに燃料を補給したり、ゴミを捨てたりするなど、さまざまなタスクを遂行する役割です。 インポスターは船を妨害し、クルーメイトを殺すことを担当します。 ゲームはリアルタイムでプレイされ、プレイヤーはチャット機能を使用してお互いにコミュニケーションできます。クルーメイトはチャット機能を使用して、インポスターを考える方法やタスクを調整する方法について話し合うことができます。インポスターはチャット機能を使用して、クルーメイトを欺いて捕まらないようにできます。 ゲームはすべてのタスクが完了するか、すべてのクルーメイトが殺されると終了します。すべてのクルーメイトが殺されると、インポスターの勝利です。すべてのタスクが完了すると、クルーメイトの勝利です。 ボーナス:私は「Among Us」が言語教育にどのように使用されるかについての考察をこちらで書いています(York、2020)。– 🧑🚀– |

ඞ Among Usのデジタルバージョン

デジタルゲームでは、私が宇宙船で「死んだふり」をする権限は完全に奪われています。ゲームは私が表すキャラクターアバターを制御する能力を奪い、代わりに私はある種の漫画のような肉のような棒、骨が左に突き出て表示されます(図2)。私は自分のキャラクターアバターを失い、新しいアバターをコントロールする権限を得ます:他のまだ生きているプレイヤーとは対話できない自分のゴーストバージョンです。

図2

ඞ Among Usのリアルライフバージョン

しかしながら、このゲームのリアルライフバージョンでは、私の行動を制御するための基本的なコンピュータソフトウェアやハードコードされたルールはありません。私が決定します。私は死んだふりをすることになっていることを知っていますが、それを実行するのは私次第です。

この場合、および上記の写真では、私はまさに期待されていることをしています。私の行動(明治大学泉キャンパスの学習スクエアの4階に横たわっている)は完全に論理的であり、むしろ、その時点で私が行うべき唯一のことは… もし私がゲームをプレイしていると知っているなら。

これがこのエッセイのテーマです。なぜ公共の場で床に横たわることが「正しいことであり、自然なこと」だったのかを説明するもので、外部から見れば私の行動はまったく逆のように見えます。

セクション2: ゲームのマジックサークル

普及型ゲームの普及的な性質

私の新入生セミナー(教養演習)では、学生たちに「ビッグゲーム」またはゲームデザインの世界では「普及的なゲーム」として知られるものを作成する課題が与えられました。これらは「マジックサークル」として知られる現実の世界とゲームの世界の境界をぼかすゲームです。したがって、これらの概念を考えてみましょう:ゲームの世界、非ゲームの世界、およびその間の障壁。

(非普及的な)ゲームのマジックサークル

ゲーム哲学とゲーム研究の中心的な概念の1つは、ゲームが非ゲームの現実的な文脈に対してどこで始まり、どこで終わるかを定義することです。

マジックサークルは、文化史家ヨハン・フィジンガが1938年の著書「Homo Ludens」で作り出した用語であり、ゲームを現実の世界から一時的に分離するものです。フィジンガによれば、マジックサークルは「通常の生活の規則が一時的に中断される一時の世界」であり、ゲームは日常の世界から独立した特別な現実を作り出すと主張しています。プレイヤーがマジックサークルに入ると、彼らはゲームのルールに従うことに同意します。これにより、プレイヤー間で共有の目的と協力の感覚が生まれ、彼らは自分の不信を中断し、ゲームの世界に入ることができます。

具体的な例として、ボクシングを考えてみましょう。ボクシングの試合を観察するだけで、次のことが明確にわかります。

- 現在プレイしているのは誰か。

- プレイ中に許可されていることと許可されていないこと。

- ゲームが行われている場所。

- ゲームが始まり、終わる時期。

これらは現実から分離された境界内に存在しています。ボクシングリングの物理的な境界はボクシングのコンテキストから非ボクシングのコンテキストを分離します。社会的な境界は、誰がボクシングに参加していて誰がしていないかを示しています。また、相互作用のルールに関する別の境界が存在し、それにより特定の手段を許可し、他の手段を割引または禁止します(つまり、ボクサーの一人が手袋に馬のくつわを入れた場合、我々が知っているようなボクシングは行っていません。彼らは詐欺を働いているので、ゲームをプレイしていません。最後に、時間的な境界は、3から12ラウンドの間、2人の競技者がボクシングしていることを示しています。時間が経過するか(または誰かが負ける)とゲームが終了します。

マジックサークルの存在については意見が分かれています。Consalvo(2009)はマジックサークルが存在しないと書き、Calleja(2012)はそれを消そうと試みました。しかし、私はゲームと非ゲームの文脈の間に何らかの境界が確実に存在すると考えています。したがって、まずそれを定義し、普及型ゲームがそれをどのようにぼかすかを考察しましょう。

普及型ゲームとマジックサークルの破壊

普及型ゲームは、ゲームの世界と現実の世界の境界をぼかすことで、ゲームのマジックサークルを壊します。これが私が学習スクエアで死んで横たわっている場合にそれはまさに起こっていることです。

上記で述べたように、従来のゲームでは、ゲームの世界は現実の世界とは異なる独立した空間です。プレイヤーはゲームのルールに従うことを約束することでゲームの世界に入り、プレイを停止するとゲームの世界から出ます。一方、普及型ゲームはゲームの世界と現実の世界の間に明確な境界がないです。ゲームの世界は現実の世界に広がり、現実の世界がゲームの世界に侵入することがあります。ゲームの世界と現実の世界の境界がぼやけることで、プレイヤーに没入感とリアリズムの感覚を提供できる一方で、ゲームがどこで終わり、現実の世界が始まるかを定義するのが難しくなります。これは素晴らしいことです(私の意見では)!Montolaら(2009)は、普及型ゲームを物理環境をゲームの世界の一部として使用し、プレイヤーに現実の世界を移動する必要があるゲームとして説明しています。

「リアルアモングアス」ゲームがマジックサークルをどのように破壊するか

それはかなり明らかかもしれませんが、「リアルアモングアス」ゲームは物理的な空間の観点からマジックサークルを破壊/拡張します。

述べたように、このゲームは大学キャンパスでプレイされ、人々が日常の活動を行っている場所でした。その結果、このゲームは現実の世界をその遊び場として占拠します。リアルアモングアスは現実の世界に浸透します。 「このエリアはゲームをするためのもので、このエリアは勉強のためのものである」という明確な区別は、ゲームのプレイヤーには存在しません。または、非プレイヤーの視点からこれを考えてみてください。彼らは私たちがゲームをプレイしていることに気づいていません。彼らが使用している空間は勉強のためのものです。これらの目的の交錯は、空間の中の人々のメンタルステート、特にプレイヤー対非プレイヤーのマインドセットに密接に結びついています(これについては間もなく見ていく予定です)。

セクション3: なぜ重要か

ゴフマンのフレームとプレイの演技

ゲームのスリルを超えて、公共の床で死んでいる行為は、広く普及しているゲームにおける私たちのメンタルステートと行動がゴフマンの「フレーム」理論と私たちの広範な社会的な相互作用とどのように関連しているかを探求するためのレンズとなります。

アーヴィング・ゴフマン(1974)の「フレーム」概念は、私たちが周りの世界をどのように理解するかを助けてくれます。ゴフマンによれば、私たちは絶えず経験を解釈するための解釈の枠組み、または「フレーム」を組織しており、これらのフレームは対話に文脈と意味を提供します。フレームは期待される行動と適切な行動を確立することで、社会的な状況を航海するのに役立ちます。ここで重要な概念の1つは、スート(1978)の「lusory attitude(遊戯的態度)」です。これはゲームをプレイする際に私たちが採用する特別なメンタルステートであり、ゲームの架空の現実を一時的な基準として受け入れる意志のある状態を指します。

これらの概念を組み合わせて普及型ゲームの固有の性質と結びつけると、面白いことが起こります。これらのゲームがゲームの世界を現実の世界とシームレスに融合させることで、これらのゲームは日常生活の確立されたフレームを挑戦し、ぼやけさせます。私の場合、床に死んで横たわる行動は大学の廊下の期待されるフレームを崩壊させます – 学生が勉強し、歩き回り、交流する場所。しかし、ゲームの共有のlusoryフレームの中で、私の行動は完全に合理的であり、亡くなったクルーメイトが役割を果たしているからです。

セクション4: 社会への影響

普及型ゲームにおけるフレームのぼやけや変化が真空で存在しているわけではありません。これは、私たちが社会全体で相互作用し、行動する方法を反映し、潜在的に影響します。異なる視点を考慮し、行動を適応させることを奨励することで、普及型ゲームは社会的な相互作用において柔軟性と共感のトレーニンググラウンドと見なされるかもしれません。または、少なくとも、日常の社会的なフレームが固定されていないことや変更できることを認識できるかもしれません… 🤔。

普及型のゲームプレイ以外で、フレームの関与を認識する重要性の具体的な例として、Lowe(2023)は、英語を第二言語とする教師がいくつかの教室の活動の参加不足や虚無感を突然認識するかもしれないと述べています。つまり、私たちは教える動作をすることをやめ、コンテンツが特定の学生には無意味である可能性があること、Pennycook(1994、p.311)が「空のおしゃべり」と呼ぶものに生徒を巻き込んでいることに気づくかもしれません。この自己認識は、教師が教育方法の効果を再評価する契機となります。従って、従来の「教師」の枠組みから外れて学生の視点を考えることで、無意味または関連のないコンテンツを特定し、より魅力的で意味のある学習体験を作り出そうと努力します。

まとめ

最終的に、私の床に死んでいる経験は、普及型ゲームにおけるメンタルステート、行動、社会的フレームの興味深い交差点を強調しています。遊戯的態度を採用すること(つまり、ゲームのルールを完全に受け入れてゲームを存在させるために)と、ゲームの世界と現実の世界のぼやけた境界を航海することで、これらのゲームは私たち自身と周りの世界との相互作用を理解するためのユニークな遊び場を提供しています。

主要なポイント:

- フレーム:私たちは特定の状況で期待される行動と意味を定義する「フレーム」を通じて世界を解釈します。

- 遊戯的態度:ゲームをプレイする際、私たちはゲームの現実を一時的な基準として受け入れる特別なメンタルステートを採用します。

- 普及型ゲーム:これらのゲームは通常のフレームをぼやけさせ、ゲームと現実の境界を挑戦します。

- パフォーマンスと誤解:プレイヤーはゲームのフレーム内で役割を演じ、外部の人は独自の「通常」のフレームでその行動を解釈し、誤解が生じる可能性があります。

Leave a Reply